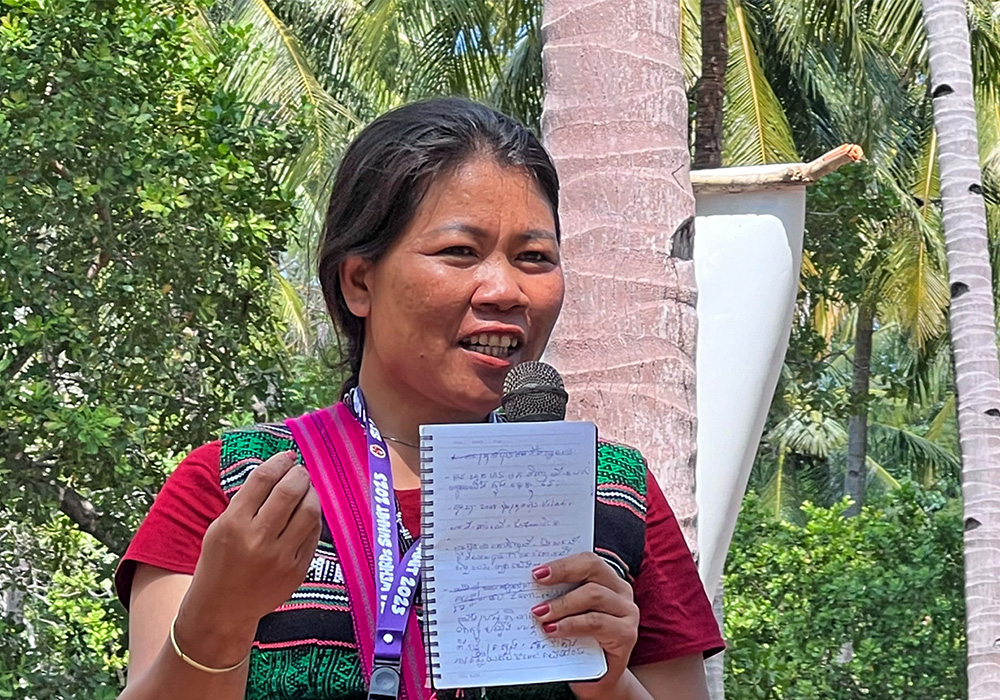

Phyrom, a proud Bunong woman leader, who joined the Women Environmental and Human Rights Defenders (WEHRD) conference in Adonara, Indonesia. (SAMDHANA/Siewyong Inthirath)

- admin

- 27 November 2023

- Feature

Women Of The Bunong Tribe: Standing Together To Reclaim Their Lands And Identity

The Phnong (or ‘Bunong’) tribe is one of the Indigenous ethnic minority groups living in Mondulkiri province, Cambodia. The Bunong are known for their intimate connection to nature and their beliefs in forest spirits that inhabite wild places and should not be disturbed.

The name of their homeland – Mondulkiri – literally means 'meeting of the hills' and this is an apt description of the local topography, which is characterised by rolling hills, lush rainforests and powerful waterfalls. Mondulkiri is home to a number of protected areas, including the Phnom Prich Wildlife Sanctuary, which was established in 1993; and the Srepok Wildlife Sanctuary, established in 2016. Together, they form two of the largest protected areas in all of Cambodia.

Phyrom is a proud Bunong woman leader who was able to join the Women Environmental and Human Rights Defenders (WEHRD) conference held in Adonara, Indonesia, in May 2023. At the conference, she shared information about her tribe's belief in dreams and their significance in farming; when the community want to begin farming a new area, they first clear a small pocket of the forest, about 4-5 metres in size. After that, they go to sleep and wait for a sign to come to them in a dream. If their dreams are positive, they will continue to clear the area for planting; if, however, they have a bad dream, it is considered an inauspicious omen, suggesting the spirits do not advise clearing the area.

The Bunong also pay close attention to signs from the natural world around them, particularly insects; when insects sing in the forest trees, the people begin clearing, mostly in the months of March to May or before the rainy season starts. They then start to plant traditional trees, fruits and vegetables such as pumpkins, chili, aubergines and ginger, etc. The tribe have their own view of when is the most favorable time to begin their planting season. Around April-May they plant on a small patch of land, then move to another, then another; this gives the soil a chance to recover. They return to each plot only after a designated fallow period, when the soil has had time to replenish its nutrients naturally.

During her childhood, Phyrom saw her area as being especially biodiverse; rich in wildlife and natural resources. Going to the forest gave her and her friends a sense of fulfilment – it was their school, their pharmacy and the centre of their spiritual life. She remembers her elders discussing traditional culture, natural resources and other issues related to the environment. She believes the tribe need to reconnect with this wisdom and consider their future, so they are prepared for whatever tomorrow may bring.

Especially for young members of the community and their families, Phyrom worries about a lack of education; the nearest school is 25 kilometres away and the road is in a poor condition. She is concerned that people in her community do not value their collective rights, and are not planning properly for the future. She has already seen big changes in recent years. Around 2000, she began to see big signs printed with ‘Land for Sale’, appearing one after the other, from village to village. Phyrom soon realised that the sale of land in their area was becoming rampant. Fast forward to today and there are communities growing pine trees on plantations financed by Chinese investors, rubber plantations run by Vietnamese investors and gold mining operations headed by Australian investors.

Over time, she has seen spiritual practices die out. Many spiritual and funerary grounds have been converted into plantations or otherwise desecrated. Their traditional practice of interval farming –allowing the land to breathe and become fertile again via natural processes – has been replaced with monocropping. Areas that were once farmed, hunted and considered sacred by the Bunong are gradually being taken away from them.

Sadly, it is not only farming practices that have been lost; over the years, many traditional local names have also been swapped for more mainstream alternatives, with pronunciation also changing. In school, when Bunong children write or speak their own names, their classmates laugh at them. As a result, many Indigenous Peoples – not only the Bunong tribe – have ended up with two names: their original name and the one they use in public. Phyrom is a traditional Khmer name; however, her son has now adopted a mainstream pseudonym, which to her sounds foreign.

At this point, Ya Yanny, Phyrom’s co-leader, sighed in affirmation. She too is upset with what outsiders are doing to traditional practices and systems. It is no longer the tribe who make decisions for themselves; instead, it is foreigners or outsiders. With the arrival of road networks and other development projects, Indigenous Peoples like Ya Yanny and Phyrom are being displaced. Fences have sprung up around newly designated properties in their area, creating literal divisions between community members and cutting off interpersonal relationships.

When community members try to get around these barriers, they are charged with trespassing or forcible entry. Many, including community leaders, have protested; they couldn’t understand why the local authorities treated them as if they were intruders, when they were in fact the original occupants of these lands. Now, it is only the individuals who have paid for deeds and titles that are recognised as owners or administrators of these lands.

In light of these growing challenges, Phyrom believes the time has come for Indigenous communities to speak out and take a stand. Recently, local authorities even attempted to re-define ‘Indigenous Peoples,’ as ‘local communities’ – another step in the process of dispossessing them of their identity and slowly removing them from their lands.

Phyrom and Ya Yanny are determined to defend their land. They intend to take concrete action together as a community, beginning with an inventory of the resources that still remain, while also mapping their boundaries and documentating exactly how their tribe has been displaced, to the point where hardly anyone is left. And they intend to pursue this advocacy with women leading from the front.

Words that begin with 'Bu’ – like Bunong and Bu Prey – connote interconnectedness; not just with each other as members of the Bunong tribe but, more importantly, with nature. This is integral to the Bunong tribe’s identity. Phyrom and Ya Yanny are two of many women environmental and human rights defenders who are embodying this ethos of togetherness, joining hands in coordinating some 55 villages in Mondulkiri province, where their Bunong tribe continues to hold their ground.