The PARARA Consortium members, including the Samdhana Institute and its partners, visited Pari Island, Jakarta during the PARARA event titled "Women's Solidarity Learning Exchange in Livelihood. (Photo by Samdhana/Naely Himami)

- admin

- 30 June 2025

- Feature

The Women and Fisherfolks of Pari Island

A series on community climate action and coastal communities

In Indonesia, fish is readily available due to the country's rich oceanic resources. As a maritime nation, Indonesia boasts a diverse array of marine life. On Pari Island, which is part of the Seribu Islands near Jakarta, fishermen catch various types of fish, shellfish, and shrimp, providing a vital source of livelihood for the local community.

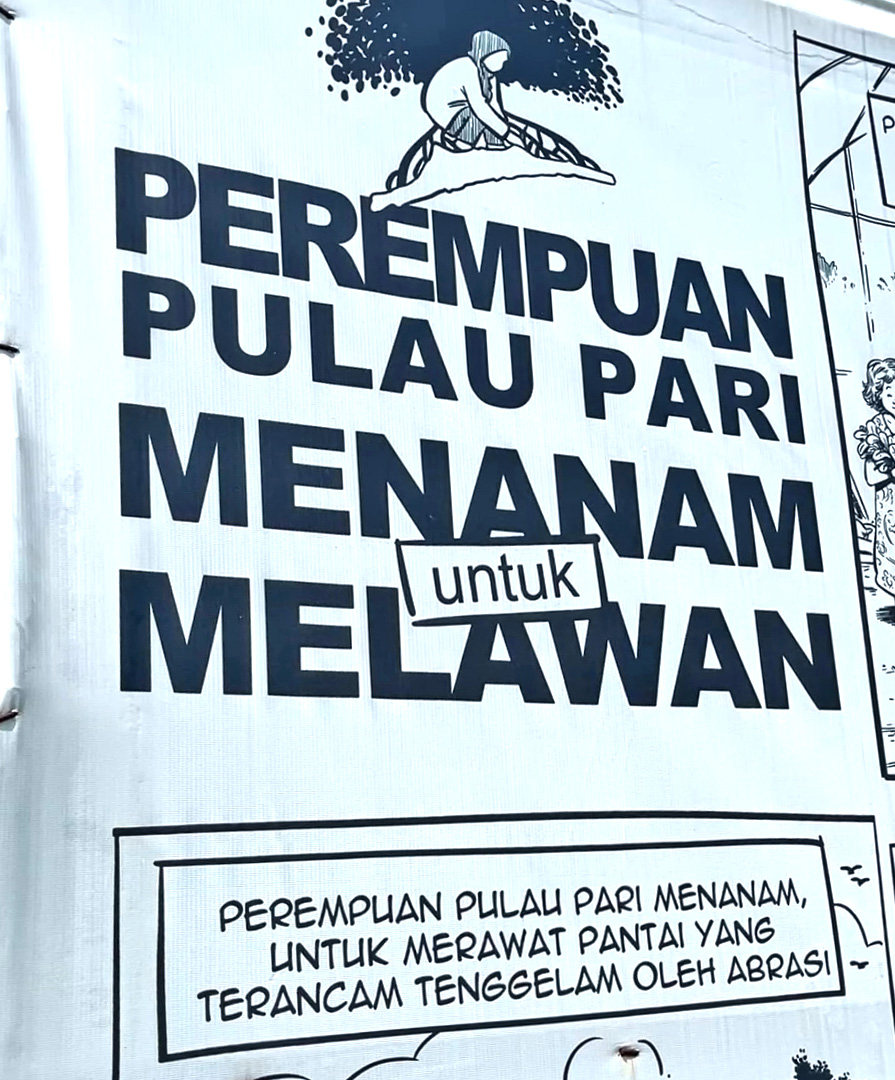

During a trip to Pari Island with the PARARA Consortium members, including the Samdhana Institute and its partners in the NLGF-VCA project, the residents shared about their struggles and efforts to keep their marine livelihoods and their living space. A total of 25 women and 2 men joined this trip, as part of PARARA’s activity on "Women's Solidarity Learning Exchange in Livelihood: Intergenerational Knowledge Transfer, Climate Change, and Human Rights Defense" which took place from May 8 to May 10, 2025. This event marks the conclusion of a series of International Women's Day events and the commemoration of World Earth Day 2025.

Young people, gender equality activists, environmental activists, local food advocates, and MSME business representatives from South Sulawesi and West Sumatra were part of the delegation who met with Pari Island residents.

One of them was Asmania, also known as Teh Aas, who shared insights about the livelihoods of local fishermen. These fishermen catch fish that are not only consumed locally but also sold at fish auctions. Additionally, their catch is marketed to fish markets in Jakarta.

Inequality of Living Space

Aas and other residents of Pari Island had lost their homes and their livelihoods due to sand mining activities and reclamation projects. The reclamation project in the waters of Jakarta has been ongoing since the New Order –also known as Orde Baru (Orba), which began in 1966 under the regime former President Suharto – era. Marine spatial planning in Indonesia is governed by the Coastal Area and Small Islands Zoning Plan (RZWP3K). This regulation is mandated by Law No. 27 of 2007, which pertains to the management of coastal areas and small islands.

Fishermen are now forced to fish farther from shore due to restrictions. Company officials patrol the area, prohibiting access to certain locations. Additionally, the developer's heavy machinery, which is used to extract sea sand for land expansion in the reclamation area, has damaged mangroves and destroyed marine life that are vital to the local community's livelihood.

"Heavy equipment damaged 40,000 mangrove plants that we planted," said Aas with tears in her eyes. "The fish died because the seawater was too hot." As fishermen now have to sail farther to catch fish, there is an increase in costs. Additionally, they often return home with very few fish or none at all.

As an alternative source of income, residents use fish aggregating devices (FADs) to catch fish and also harvest seaweed. Locally called rumpon, these devices are placed on the seabed and are used by fishes as breeding places or habitats.

Resa Fondania, a Project Assistant at WWF Indonesia, affirmed these issues that created a great challenge for Pari Island, including climate change, and waste management problems. According to her, much of the waste on Pari Island originates from nearby Jakarta.

"The waste dumped into the river [in Jakarta] flows to the sea and reaches Pari Island, damaging the coral reef habitat and decreasing biodiversity," said Resa. She said that this could also increase threats to humans, as there could be a buildup of toxins in the animals, jeopardizing public health when they are consumed.

There is also an inequality in access to livelihoods in Makassar, South Sulawesi. The fishermen depend on the punggawa or moneylender for capital loans through profit-sharing agreements. Consequently, they are required to sell their catch to the punggawa, at prices set by the punggawa, which usually means that the fishermen do not earn enough money.

"Some fisherfolks are even forced to use bombs to get fish because they have to deposit money to the officials, to the capital providers," said Nuraeni from the Fatimah Az-zahra Women's Fishermen Group (KWN), Makassar, South Sulawesi.

Women Fight Back

Women on Pari Island have taken action to reclaim their living space. In 2019, Aas and other women formed the Pari Island Women Farmers Group (Kelompok Wanita Tani or KWT). Alongside other residents, they successfully blocked heavy equipment, compelling the corporation to withdraw its machinery intended for clearing mangroves, reclaiming land, and dredging the shallow areas around Pari Island.

They have also filed their complaints against the developers to the relevant authorities, including the DKI Jakarta Provincial Public Works, the Spatial Planning and Land Agency, and even the Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK). They hope that these efforts will lead to the cessation of reclamation practices.

The women of Pari Island also manage tourism independently as an additional source of income. Many residents have built lodgings and food stalls, offering various tourist activities such as scuba diving, snorkelling, and boat tours. Meanwhile, some residents continue to fish, catching kerapu (grouper), squid, and shrimp.

"From this [ecotourism] business, we are able to provide jobs such as catering, homestays, bicycle rentals, boats, tour guides, snorkeling too,” said Mustaghfirin, also known as Boby, a resident of Pari Island who now has a tourism business on Pari Island. “The fishermen also benefit from the presence of tourism here as the price of the fish is now higher."

The women's group on Pari Island built a greenhouse where they grow various types of vegetables, including kale, chilies, tomatoes, and spinach. Despite the limited space for planting, the residents are able to harvest enough produce for their own consumption. In fact, they generously share their food with both members and non-members of the Pari Island women’s group.

It is also part of their strategy to avoid being evicted from their homes, as their land certificates are controlled by Bumi Pari Asri, which claims to be the “legal landowner.” This company is employing various tactics to evict the residents. Unfortunately, many individuals who are fighting for their land rights find themselves criminalized in the process, with some even facing jail time.

"I was once in prison for 7 months for fighting against the company [Bumi Pari Asri]. They offered me a salary of 16,000,000 if I joined them," said Boby, who was also offered a house, billions of rupiah, and a good position. "But I refused all of that. Because I remembered my friends on Pari Island. They want to live decently and be recognized by the state."

Thanks to the support of the Lembaga Bantuan Hukum or LBH, Boby was released from prison. Currently, there are various legal aid organizations that assist the community, particularly those who are less fortunate and can’t afford to pay for legal representatives. These organizations offer free legal aid, including support in a range of cases, both criminal and civil. One such organization is LHB APIK Semarang, which has been providing legal assistance and defence to communities in the coastal areas of Central Java.

"We provide free legal aid,” said Rara Ayu from LBH APIK Semarang. “We receive more than 35 cases per month. We are assisted by friends from the Demak Regency and Semarang City communities in Central Java. They are paralegals who have received training on how to assist the communities,"

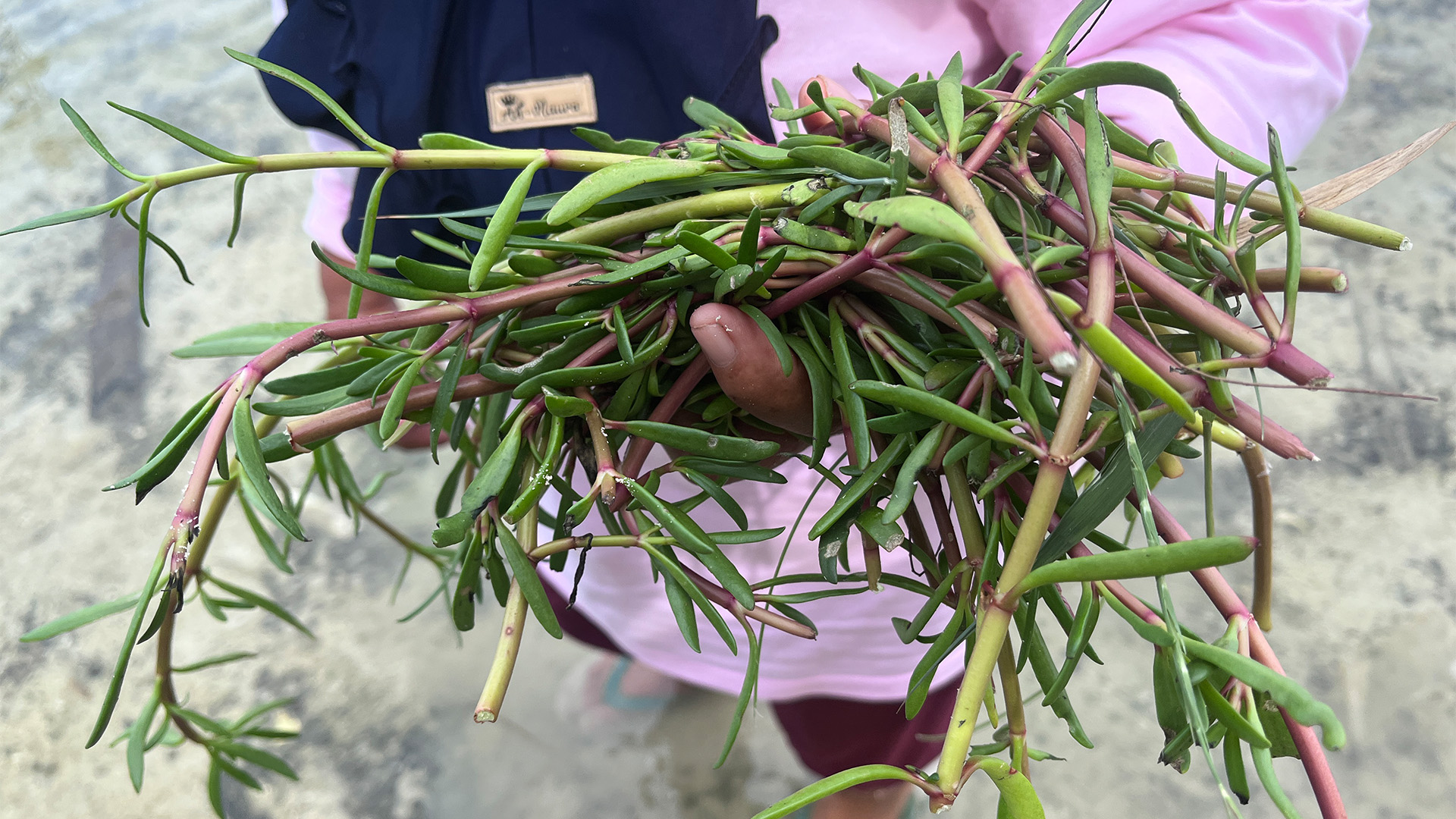

Additionally, with the support from NGOs like WALHI and KIARA, women on Pari Island have been actively involved in rehabilitating mangroves since 2010 to restore the ecosystem that was damaged by sand mining and land reclamation.

This rehabilitation allows marine life to flourish once more. Local residents then process part of their catch into products for tourists, such as fish chips and salted fish. They also sell bloncong (mangrove shellfish). The effort also includes the reintroduction of sea plants krokot or gelang, which can be made into soup.

Women from the Fatimah Az-Zahra Fisherwomen's Group (Kelompok Wanita Nelayan or KWN) in Makassar, South Sulawesi, have engaged in a similar initiative. With the group’s capacity-building programs, they train women how to process seafood into snacks and package them for sale throughout the city of Makassar. This venture serves as a source of livelihood, helping them break free from dependence on the punggawa. Additionally, they receive advocacy support and education on their rights, including legal protection for children, women, the elderly, and individuals with disabilities.

The Future of Marine Conservation Efforts

Although currently limited in scale, the dedicated efforts of the residents of Pari Island and the women in Makassar offer a promising strategy to protect and conserve the environment and marine biodiversity, which are essential for the survival of future generations.

The young people who attended the meeting, such as members of the organization Climate Rangers, expressed their commitment to protect the environment from the impacts of climate change and extractive activities. The Climate Rangers is a youth-led organisation operating in 15 cities around Indonesia, and fights for intergenerational climate justice and a just energy transition. They participate in climate forum, create social media content and campaign to raise awareness in their communities. They also encourage policymakers and government officials to make decisions that will help safeguard the environment.

"We can also voice our concerns [regarding climate] and provide information or exchange ideas with other friends to fight for climate justice together," said Febri from Climate Rangers.